Why on earth does David Cameron feel the need to call for new digital powers for the security services when they are only beginning to use the ones they already have? Suppose you wanted personality profiles of a quarter of the population of England? Turns out you can mine them from Facebook with publicly published algorithms. About half the adult population of England uses Facebook at least once a month. About a quarter of us have “liked” more than 250 things there. So it’s really disconcerting to discover that completely banal acts on Facebook can add up to a quite detailed psychological profile.

Cambridge and Stanford scientists have discovered that Facebook likes can be mapped on to a personality profile used in clinical psychology so that you can get a remarkably accurate estimate of people’s scores on five well-established dimensions of personality just by analysing several hundred Facebook likes.

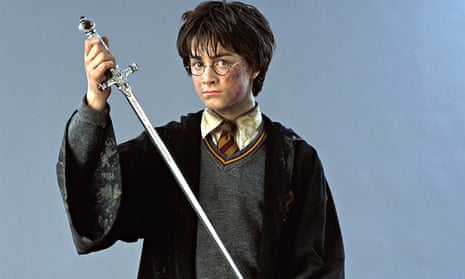

What makes this particularly spooky is that the “likes” in question are not particularly personal ones. There are, says David Stillwell, one of the researchers, something like 100,000,000,000 likes registered in Facebook’s databases. So the team ignored all the personal things that were liked, and concentrated on those few Facebook pages with more than 100,000 likes. These are almost by definition pop culture, rather than expressions of the subtleties of individual personality: to know that someone likes tanning, or Harry Potter, doesn’t really distinguish them from millions of other Facebook users. Except that, in aggregate, and given enough data, that’s exactly what it does.

The researchers started with 86,000 subjects who had filled out the 100-question personality profile – and this, of course, was done as another app on Facebook – and whose personality scores had been matched by algorithms with their Facebook likes. They then found 17,000 who were willing to have a friend or family member take the personality test on their behalf, trying to predict the answers they would give.

The results, from most humans, were stunningly inaccurate. Friends, family and co-workers were all less able to predict how someone would fill out a personality test than the algorithms that had been primed with the subject’s Facebook likes. With only 10 likes to work on, the computer was more accurate than a work colleague would be. With 150 likes, it described the subject’s personality better than a parent or sibling could. And with 300 likes to work on, it was more accurate than a spouse.

Not all the details of this research are public. Stillwell says: “Our algorithms are published. But they need the numbers that show that tanning is related to extroversion … and those have not been published. We do have a service available to commercial companies, but among the conditions is that people have to give consent, and to know what is being done with their data.

“No one”, he adds, “should have had a prediction made about them without their knowledge.”

But if the algorithms are public there is nothing to stop the security services repeating the research and coming up with their own numbers. Should they do this, they will have a mine of data on our inmost characters of which earlier secret police forces could only dream. And it would all be collected openly, legally, and with the co-operation of everyone who ever liked a film or a popular thought on Facebook.

The researchers are worried about the implications for privacy when this data falls into the hands of advertisers or recruitment companies. They are quite right in this. But it is much harder to defend such information against sifting by the state. We are only beginning to grasp how big data can change the world – but it is leading us into a world where, after the suburban murderer is caught, after the neighbours say “he always seemed so quiet and polite”, it won’t be the things he said on social media that betray his real personality – but the things he merely liked.